Contradictory demands risk undermining European Universities Initiative, say Silvia Gomez Recio and Chiara Colella

The European Universities Initiative has changed the face of higher education in Europe since its inception in September 2017. The 44 alliances set up under the EUI so far—set to become 60 by the end of 2024—are giving universities a new identity at the European level and a higher profile in the EU debate than ever before. This brings both opportunities and challenges.

Supported by funding from the EU’s Erasmus+ scheme, these alliances of universities across Europe are pioneering new models of cooperation, implementing digital platforms, innovating in teaching, and boosting collaboration with other sectors and their communities. There is less focus, however, on the challenges they face. Deadlines are tight, winning funding is a constant struggle, and alliances operate in an extremely competitive environment.

It is important to recall that the EUI started as a pilot: success and failure should be equally valuable. So what is expected of the EUI? How have alliances evolved over time? And does their format match their objectives?

The initiative launched with the aim of transforming how universities in Europe operate and collaborate. This was a grand enough ambition, but since the second round of alliances kicked off in 2020, the world has become less predictable, reshaping objectives and increasing demands for universities to address societal challenges. Combined with their political prominence, this has left alliances facing expectations to deliver on many more fronts than originally envisaged, from immediate crises such as the war in Ukraine to long-term goals such as the green transition.

The expanding expectations pull in multiple directions and risk diverting alliances from their original missions, so that their main objective becomes winning enough funding to continue. This would put them in a compromising position when called to share their views on the EUI’s future and shows why it is important to distinguish alliances’ role from that of university networks, and ensure that those leading policy advocacy are not financially bound by the initiative.

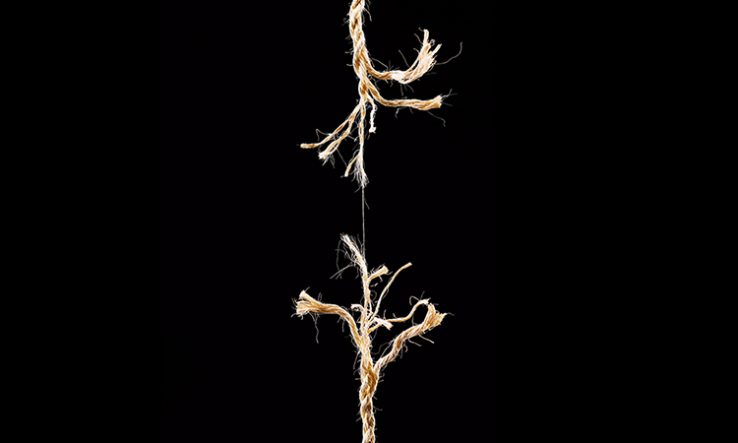

What’s more, asking alliances to achieve everything expected with four-year Erasmus+ grants is asking a great deal. The mismatch between ambitions and means puts an enormous strain on the alliances, the institutions involved, and the people working to make them a success.

All this puts the EUI’s original objectives at risk of being submerged by political negotiations, financial shortcomings and governance challenges. Instead of building something unique, the alliances would end up putting a fresh coat of paint on an old house.

The EUI should go back to its roots and reflect on its first years. If there is a need for more time and different tools, then ways should be found to provide them.

Multiple partnerships

Alliances are charged with transforming how universities operate in many areas: innovative education, research cooperation, new mobility models. But they are expected to do so within a single configuration of partners, whereas the institutions that make up alliances have other, separate partnerships and strategies. It is important that the EUI is not seen as a panacea, and that policymakers and institutions keep an open mind on complementary forms of cooperation and bottom-up initiatives that might achieve the same goals, perhaps even better.

Similarly, many alliances are overlaid onto pre-existing university networks. These structures need to work synergistically, with differences understood and preserved to avoid duplication of effort and to foster positive complementarities. While alliances experiment with new models of cooperation, networks represent the interests of universities in Europe with an independent voice, much broader scope and more flexibility.

As the final reports from the first alliances from 2019 are being prepared, several EU studies have been launched to evaluate the EUI. It’s important to use the right tools. Numbers and quantitative indicators—of students travelling, programmes launched or joint activities—will not capture transformations in how institutions are collaborating, nor reveal how cross-institution working enriches education and research. They will not show how exposure to different perspectives and experiences changes how staff respond to challenges, nor how the power of exchanging and working together at such a level of integration helps institutions achieve more than any could alone.

With more alliances planned, more still expected and the negotiations for the next EU budget period, starting in 2028, already on the horizon, the EUI is at a crucial moment. This is the time to reflect on where it is going, and how to use everyone’s resources in the best way to ensure its success.

Silvia Gomez Recio and Chiara Colella are secretary general and policy officer, respectively, at the Young European Research Universities Network

This article also appeared in Research Europe