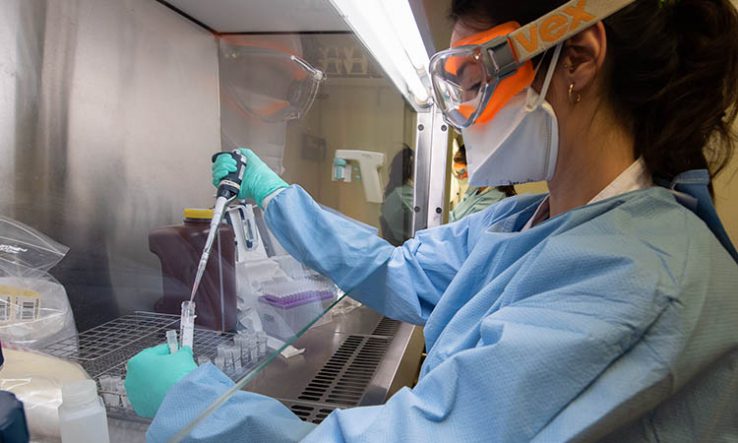

Image: Hospital CLINIC [CC BY-ND 2.0], via Flickr

Institutions offer staff and supplies to help NHS as Covid-19 cases surge

Universities have taken up positions on the frontline of the battle against Covid-19, offering up researchers and vital equipment to help the National Health Service fight the coronavirus.

Amid surging case numbers and concerns over the lack of ventilators, personal protective equipment and diagnostics technology in the NHS, UK institutions have stepped up to provide supplies and expertise. The moves come as the number people in the UK confirmed as having the virus reached 51,608, including prime minister Boris Johnson, who has since been admitted to intensive care.

University College London, located at the UK epicentre of the pandemic, has provided 16 polymerase chain reaction machines normally used to carry out research into drugs for cancer, dementia and infectious diseases, which it says will enable thousands more people to be tested for the virus.

“What we are facing now is something that is unprecedented in our lifetime, that is a major civil upheaval on the scale of wartime—and it’s absolutely imperative that everybody plays their part in this,” said David Lomas, UCL’s vice-provost for health.

“Universities are a fabulous resource of very talented, clever people, skills, science, reagents and resources—and it is critical that they are all thrown into the battle and offered up in order to make a difference in this terrible time.”

Engineers at the university have also teamed up with carmaker Mercedes and clinicians at the UCL Hospitals NHS Trust to create a non-invasive breathing aid that can be “produced rapidly and manufactured in the thousands”. The government has placed an order for 10,000 of the devices, which should help alleviate some of the pressure on the health service for ventilators.

UCL was also among the first institutions to release all clinical staff—including newly qualified medical students—from academic and research responsibilities so they could move to frontline care duties.

The Francis Crick Institute has also repurposed its laboratory facilities by creating a makeshift facility to test NHS staff and patients for coronavirus.

“Testing is an essential part of the national effort to tackle the spread of Covid-19. We wanted to use our facilities and expertise to help support NHS staff on the frontline who are battling this virus,” said the institute’s director, Paul Nurse.

“Institutes like ours are coming together with a Dunkirk spirit—small boats that collectively can have a huge impact on the national endeavour.”

The announcements came amid widespread concern over the availability of testing across the NHS, with many healthcare workers self-isolating with suspected symptoms or family members who are ill. Health secretary Matt Hancock has since revealed plans to scale up testing to 100,000 a day with the help of universities, industry and the NHS.

But with universities across the UK shutting down labs in accordance with the government’s social-distancing guidelines, there are fears that research will be delayed and careers affected.

Lawrence Young, a professor of molecular oncology and pro-dean of Warwick Medical School, is at the forefront of his university’s response to the crisis, which has so far included the establishment of a testing centre at the local hospital and a Crisis Research Response Team to make use of the university’s facilities and expertise.

“It’s a massive diversion,” he admitted, “and it’s hard to keep things going. Like many of us, I’m in the middle of writing grants—but all the deadlines are being shifted so we’re all worried about what this means for the continuity of our research. That’s a big worry.”

Much of the impact will rest on research funders, says Lomas.

“We’re trying to work out from funding bodies whether they will give extensions to salaries for people who will have to work at home for three months and therefore can’t do their research,” he said.

This, he explained, is a “murky issue”, with some funders more generous than others.

Charity funders such as the British Heart Foundation and Cancer Research UK are facing financial issues of their own after the closure of their shops. Many have delayed or postponed some of their funding decisions.

Like Lomas, Young is uncertain what the future holds.

“As we look forward…to the time we start up again, what type of structures do we put in place and how is everything going to start to rev up again? Because the impact is going to be so devastating.”

These questions will become increasingly important as the weeks in lockdown continue.

This article also appeared in Research Fortnight