Asking researchers to show their work creates both opportunities and risks, says Christopher Brown

The coronavirus epidemic has been a vivid illustration of the value of open science. Large publishers such as Elsevier, Springer Nature and Wiley have removed paywalls to recent studies related to the virus. Equally important has been openness earlier in the research process, as researchers worldwide have shared samples and data in the race to understand the virus and develop a vaccine.

This is another example of how, since the early 1990s, the movement for open access publications has broadened to become one for openness in research in general. For universities and researchers this is becoming the way they keep track of their tests, results, calculations and ideas.

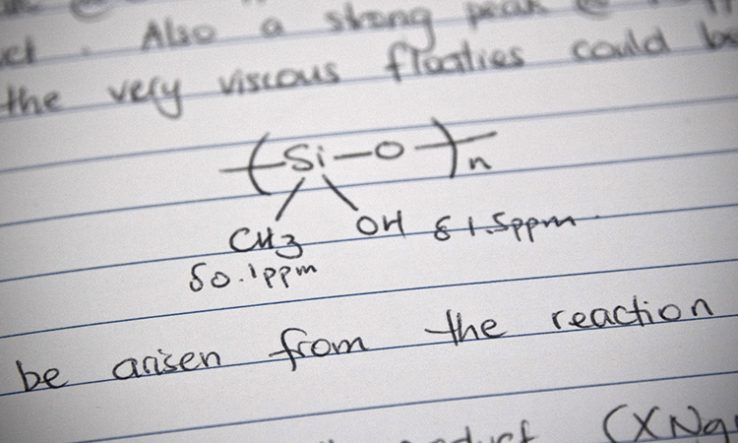

Noting down findings in a digital and shareable notebook accelerates discovery and helps reproducibility. Problems with notebooks also often reveal flawed studies, as shown when the Nobel prizewinning American chemist Frances Arnold retracted a paper on enzymatic synthesis in January when it turned out that her lab’s research notebook was missing data.

Spoilt for choice

All UK universities are in the process of adopting some sort of electronic research notebook. However, implementation is proving bumpy.

Academics are paralysed by choice and dazzled by programs that offer specialist, discipline-specific features, when in fact all they really need is a basic, reliable and secure documentation platform.

At the same time, research groups are becoming increasingly multi-disciplinary, with diverse workflows, interests and preferences. The upshot is that institutions struggle to find a product that will satisfy everyone.

Researchers’ differing needs has led to different solutions being adopted across groups. This is especially challenging for IT departments that find themselves faced with myriad tools and systems to test, procure and support.

Universities are also fearful of disruption. Committing to an off-the-shelf service over which they have little control is a big step, and it can be painful to switch should that service prove unsuitable.

Openness also brings security concerns around the risk of digital data being stolen or researchers being scooped. A publish-or-perish culture, where journal papers are the main metric of career success and publishing first is everything gives researchers an incentive to keep their notes close to their chests.

Another trepidation around introducing research notebooks constitutes intellectual property rights and patenting. Some research notebooks, but not all, give authors and witnesses the option of obtaining a patent for an invention through a stringent sign-off process. Some researchers also worry about having their early-stage research taken out of context or referenced in the wrong way.

Notes and queries

Over the past year, myself, along with others at Jisc have worked with many universities to tackle these issues and understand how we can best implement open, digital research notebooks.

To get a better idea of which tools work best, the University of Glasgow, together with Jisc, has run workshops in Glasgow, Sheffield, London and Durham. These have been led by researchers, rather than suppliers.

Based on these workshops, we have drawn up a list of requirements to help universities and researchers select a tool that meets their needs and policy requirements. A Jisc discussion forum was also set up to bring people together around this topic.

In the coming months, Jisc will be looking to develop a procurement framework for research notebooks. This will be an open framework, where vendors can submit tools for assessment.

Jisc will assess the tool and if it measures up it will be added to the framework. Such a framework will help institutions review and assess electronic lab notebooks and help with the adoption of open standards and interoperable solutions.

Most of the challenges in getting an electronic notebook right are human and organisational. If it was simply a case of installing software, their use would be commonplace. In reality, it requires careful consideration and evaluation that can’t be rushed.

Christopher Brown is senior co-designer at Jisc, where he is leading on supporting universities to switch to digital notebooks.